Complaints about Rolling Stone's Tsarnaev profile reveal underlying stereotypes.

by Dr Ronald Crelinsten

The controversy over the cover of the current issue of Rolling Stone reveals a lot about how we think about people who commit acts of terrorism and violence.

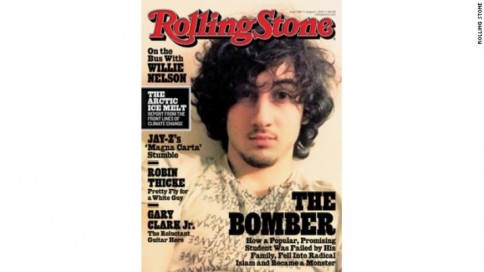

The lead story is about Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the younger of the two brothers who allegedly placed pressure-cooker bombs at the finish line of the Boston Marathon last April. The thrust of the story is how a “good person” became a monster despite all outward appearances that he was a good kid like everyone else. The cover picture is that now-iconic photo of Tsarnaev as a doe-eyed, tousle-haired youth, looking softly at the camera with a look of gentle innocence.

The outcry was immediate, not only from the mayor of Boston and survivors of the bombing, but also communications scholars who criticized the choice of cover as not only insensitive, but misleading. How could the editors have depicted a killer in such a way, especially to the youth who read the magazine? Boston-area residents in particular complained that the cover made the young man look like a rock star. It didn’t seem to matter that the same photo had already appeared widely in the media, including the front page of the New York Times.

Janet Reitman’s piece helps the reader understand how someone who seemed to fit in so well and seemed so “normal” could end up committing such terrible violence, as good investigative journalism is supposed to do.

The term “terrorist” has long served as a pejorative label. It is usually used to indicate that the bearer of the label is different from other people, excluding them from the community, the society, the polity, the nation, the civilization or even the human species. It is like other exclusionary labels, such as “criminal,” “barbarian,” “infidel,” “monster.”

Three similarly pejorative words that have entered the English language are “thug,” “assassin” and “zealot.” All three derive from the names and practices of historical religious terrorist groups: Hindu, Muslim and Jewish respectively.

This association with atrocity, barbarism, cruelty or inhumanity leads to an equation of “terrorist” with “enemy,” “outsider” or “criminal.”

Politicians often reinforce such us/them attitudes. Notable examples include former US president George W Bush’s post-9/11 injunction that “either you are with us or you are with the terrorists,” or former public safety minister Vic Toews’ controversial remark in Parliament that an opposition MP “can either stand with us (the government) or with the child pornographers.”

When someone uses threat and violence as a communicative tool to achieve things that we agree with or think they deserve, then we refuse to apply the label “terrorist” because of the negative connotations associated with the word. That is why one person’s terrorist is another person’s freedom fighter.

For many years, I taught a university course on biological and psychological theories of crime. In this course, I asked students to do a photo project in which they had to make a photograph of themselves as a criminal and as a non-criminal, using theories from the course. They were also asked to provide a “baseline photo” of themselves before their experiment. Some students simply used that same photo as their “non-criminal photo,” suggesting that their self-image was intimately tied in with the idea that they could never possibly be a criminal.

Janet Reitman’s piece in Rolling Stone helps the reader understand how someone who seemed to fit in so well and seemed so “normal” could end up committing such terrible violence. This is what good investigative journalism and good social science research is supposed to do.

The widespread anger and revulsion at the Rolling Stone cover is a reflection of how much this professional norm has been and continues to be undermined, especially since the 9/11 attacks. One commentator describes it as a culture of denial, self-censorship and basically just not wanting to know.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s remark after the Boston Marathon bombing that it was not the time for “doing sociology” reflects the same anti-knowledge trend. In this atmosphere of denial and accusation, explaining is considered the same as justifying. From this perspective, any attempt to understand what really happened risks opening the door to sympathizing with the perpetrator. Sympathy or understanding is simply not acceptable in a Manichaean world of us vs. them.

One can only hope that people of all ages and backgrounds read the entire Rolling Stone article and come to their own informed conclusions.

Copyright (c) 2013. Ronald Crelinsten. Reprinted with the permission of Ronald Crelinsten.

© Copyright 2013 Dr Ronald Crelinsten, All rights Reserved. Written For: StraightGoods.ca

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.